IIEA: Who Owns our Water in Europe? And Does it Matter?

0 Comments

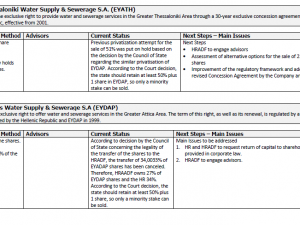

An insightful article published on the site of the Institute of International and European Affairs which explains the dynamics of the water management “war” in Europe and mentions also the greek case.The Irish government is currently in the process of centralising the State’s water services into a single entity to be known as Irish Water. The new authority will be structured as a utility company, and will be housed within Bord Gáis, the state-owned gas and energy provider. Its first task will be the nationwide roll-out of water meters, in advance of charges for domestic water supply being introduced in 2014. The reforms have led opposition spokespeople to raise the spectre of privatisation of water services in Ireland, although current Irish law guarantees that water supply will remain in public hands. The Minister responsible, Fergus O’Dowd, has strongly denied that privatisation is on this Government’s agenda. However the utility model and the introduction of charges have led some to suggest that privatisation will in the future become a logical next step. It could be said that most of the difficult work that would be involved in privatising water is now being done: moving water services from municipal and central government control into a commercial enterprise, albeit state-owned; installing meters in 1.3 million households to allow for domestic charging; creating a customer-supplier relationship between the water utility and every water user in the state. Once all of this heavy lifting is out of the way, a change in the ownership of the utility could be effected relatively easily. The Minister is right to point out that across Europe public ownership of water services is the rule rather than the exception, although this is not to say that there isn’t significant private involvement in water and sanitation. The system in place in England and Wales stands out as an example of a completely privatised approach. In France about 70 per cent of the population are supplied with drinking water by a private operator, and French water companies also have a significant role in water services in Spain. Water systems in Europe have evolved over the centuries with the public and private sectors taking the lead to a greater or lesser extent at various times in different countries, so it’s no surprise to find heterogeneity in ownership models across the EU, and even within Member States. Although the EU is ostensibly neutral on the question of water ownership, there has recently been a debate on whether the European Commission is promoting privatisation through the back door, through its role in framing bailout programmes for financially distressed Member States, and through its proposals for a new Concessions Directive governing certain types of public-private partnerships. In the case of bailout agreements, the Commission has been accused by campaigners (including labour unions and environmentalists) of insisting on privatisation programmes that include the sell-off of municipal water companies. In Greece the bailout agreement requires the selling off the State’s majority stakes in the already part-privatised Athens and Thessaloniki water and sewerage companies, while Portugal is under pressure to dispose of its state-owned water company. The Commission does not admit to actively promoting water privatisation for its own sake in these bailed-out countries, but campaigners point to its history of favouring privatisation in development aid agreements and international trade negotiations. The Commission can maintain its officially neutral stance on ownership of water services by pointing out that the privatisation measures are being carried out by the insolvent national governments themselves in order to raise money to keep other public services running. More recently, the proposed Concessions Directive has become part of this debate. The Directive is seen as necessary to regularise the way public authorities in Member States enter into partnerships with the private sector to provide services of general economic interest. A contract to operate public water infrastructure is a good example of a concession, and other examples include toll roads, waste disposal and energy generation. The Commission sees as a loophole the fact that there are no specific rules governing the award of such contracts, giving rise to risks of fraud, favouritism and lack of transparency. While the proposed text restates that, in keeping with Article 345 of the Treaty, nothing in the Directive will prejudice Member States’ own system of property ownership, it also talks of “a real opening up of the market” in respect of water, energy, transport and postal services. It is not only this language but also fears about the practical operation of the Directive which have led campaigners to class it as another attempt to promote privatisation of water. The general concern is that the conditions imposed by the Directive will result in a situation where public authorities find it easier and less legally risky to tender out concessions for water supply rather than providing the service themselves. As with Minister O’Dowd in Ireland, Internal Market Commissioner Barnier has been on the defensive against such claims, denying that the Directive will have any such effect. In a statement on 23 January 2013 he affirmed that the proposed Directive will “not lead to forced privatisation of water services. Public authorities will at all times remain free to choose whether the provide the services directly or via private operators.” This clearly did not settle the matter as a month later he took the somewhat unusual step of issuing a joint statement with Environment Commissioner Potocnik to the same effect. This followed a meeting of the European Parliament’s Internal Market and Consumer Protection Committee (IMCO) at which he pledged to make changes to the proposed text to clarify its intentions: In response to certain false accusations, allow me to be perfectly clear, precise and formal: the Commission is not seeking in any way whatsoever to privatise water management – neither today nor tomorrow. This directive does not aim and will not have the effect of bringing about a forced privatisation of drinking water supply services. I am willing to make the necessary clarifications to the text in the three-way talks. The Committee, having at an earlier meeting rejected a proposal to remove water from the remit of the Directive altogether, voted to get the trialogue underway. It remains to be seen what clarifications the Commissioner is willing to offer as part of this process, but IMCO’s rapporteur, Phillipe Juvin (EPP/France), is hoping for agreement that the text will include a solemn statement that water privatisation is not intended. The political pressure that has caused the Commissioner to take such pains to clarify his intentions demonstrates the importance placed on public ownership of water in many parts of Europe. A civil society group led by the European Federation of Public Services Unions (EPSU) and comprising labour unions as well as public water operators and environmentalists is leading a Citizens’ Initiative which has attracted more than 1.2 million signatures since September 2012, calling for guaranteed water and sanitation for all citizens and an end to liberalisation of water services. The vast bulk of these signatures have come from Germany, but the campaign is not far off reaching the required numbers in seven Member States. Campaigns are also underway to “remunicipalise” private water services, particularly in France. What does this debate about water ownership mean for water policy, particularly the resource efficiency agenda that is central to the Commissions’s Blueprint to Safeguard Europe’s Waters? Ensuring the full implementation of water pricing with incentives for efficiency is a key objective of the Blueprint. The current experience in Ireland is a demonstration that in many cases the policies required to promote efficient use of water are often the same as those required to prepare public water systems for privatisation. Public fears that metering and full cost recovery are Trojan horses for selling off of water services cannot be lightly dismissed, given the history of similar policies in the waste sector, for example, and the less than convincing claims by European authorities to be entirely neutral on the question. However by the same token there is nothing to suggest that, with the right policies, resource efficiency cannot be maximised while keeping water services in public hands. The efficiency agenda will in any case require a great deal of public goodwill – this often scarce resource might be maximised if populations can be convincingly reassured that they will retain choice in the ownership model of their water services.

Note: As an independent forum, the Institute does not express any opinions of its own. The views expressed in the article are the sole responsibility of the author.